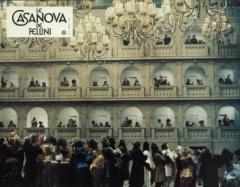

Il Casanova di Federico Fellini

During the Venetian carnival Giacomo Casanova agrees to show his amorous valor with Sister Magdalena and thus please the woman’s voyeur lover, the French ambassador from whom Casanova hopes to gain benefits. But he is arrested by the Inquisition on charges of black magic. He escapes from the Piombi prison and is in Paris as a guest of the Marquise d’Urfé who wants to obtain from him the secret of immortality. Then Casanova leaves Paris and resumes his frenzied activities as a seducer. Among his loves is the unhappy one with Henriette, who makes him despair and abandons him. In Rome he participates in an amatory contest with a Pololano, winning it. In Rome he also meets the pope and his mother, who by then has little interest in his fortunes. Finally, old age, employment as a librarian, his charm fading, the oblivion of the courts, until the loneliness of a dance with a mechanical doll, a memory of an increasingly distant past.

Crew

Director: Federico Fellini

Subject: loosely based on “Storie della mia vita” by Giacomo Casanova

Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Bernardino Zapponi

Photography: Giuseppe Rotunno (Technicolor)

Cameraman: Massimo Di Venanzo

Assistant Cameraman: Wolfgango Soldati, Bruno Garbuglia

Music: Nino Rota

Conductor: Carlo Savina

Songs: “La grande mouna” by Tonino Guerra, “La mantide religiosa” by Antonio Amurri, “Il cacciatore di Wurtemberg” by Carl A. Walken

Verses in Venetian dialect: Andrea Zanzotto

Set design: Federico Fellini

Set design: Danilo Donati

Costumes: Danilo Donati

Assistant costumes: Gloria Mussetta, Raimonda Gaetani, Rita Giacchero

Architect: Giantito Burchiellaro, Giorgio Giovannini

Set design assistant: Antonello Geleng

Editing: Ruggero Mastroianni

Editing assistant: Adriana Olasio, Marcello Olasio, Ugo De Rossi

Assistant directors: Maurizio Mein, Liliana Betti, Gerard Morin

Editing secretary: Norma Giacchero

Production inspector: Gilberto Scarpellini, Alessandro Gori, Fernando Rossi

Furniture: Emio D’Andria

Sound: Oscar De Arcangelis

Sound assistants: Franco De Arcangelis, Massimo De Arcangelis

Mixage: Fausto Ancillai

Choreography: Gino Landi

Choreography assistant: Mirella Agujaro

Scenotechnician: Italo Tomassi

Paintings: Rinaldo Geleng, Giuliano Geleng

Drawings for the magic lantern: Roland Topor

Sculptures: Giovanni Giannesi

Makeup: Rino Carboni (Giannetto De Rossi and Fabrizio Sforza for Donald Sutherland)

Hairstyling: Vitaliana Patacca

Assistant hairstylists: Gabriella Borzelli, Paolo Borzelli, Vincenzo Cardella

Special effects: Adriano Pischiutta

Producer: Alberto Grimaldi

General Organization: Giorgio Morra

Production Manager: Lamberto Pippia

Production assistant: Alessandro von Normann, Mario Di Biase

Production secretary: Titti Pesaro, Luciano Bonomi

Cast

Donald Sutherland : Giacomo Casanova

Tina Aumont : Henriette

Cicely Browne : the Marquise Durfé

Carmen Scarpitta : Mrs. Charpillon

Diane Kourys : Mrs. Charpillon

Clara Algranti : Marcolina

Daniela Gatti : Giselda

Margareth Clementi : Sister Magdalena

Mario Cencelli : Dr. Mobius the entomologist

Silvana Fusacchia : another daughter of the entomologist

Chesty Morgan : Barberina

Adele Angela Lojodice : the mechanical doll

Sandra Elanie Allen : the giantess

Clarissa Maryè Roll : Annamaria

Alessandra Belloni : the princess

Marika Rivera : Astrodi

Angelica Hansen : hunchback actress

Marjorie Belle : countess of Waldestein

Marie Marquet : the mother of Casaova

Daniel Emilfork-Berestein : Du Bois

Luigi Zerbinati : the Pope

Awards

1976

Oscar for best costume design

1977

Silver Ribbon for best cinematography

1976-1977

Silver Ribbon for best set design

1976

Silver Ribbon for best costumes

1977

David di Donatello for best music

1977

Oscar nomination for best non-original screenplay

BAFTA Award (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) for best set design

BAFTA Award (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) for best costume design

BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards) nomination for best cinematography

Peculiarites

“At first I had thought of casting Gian Maria Volonté in the role of Casanova. It would have been beneficial to the Italian actor, after so many tormented figures who had made humanity leap forward, to play a character destined, by contrast, to make it leap backward, but successive postponements had led to a breakdown of contracts. I had thus entrusted the role of Casanova to Donald Sutherland, a sperm candelon with a masturbator’s eye, as far removed as one could imagine from an adventurer and ladies’ man like Casanova, but a serious, trained, professional actor.”

(Fellini. Telling about myself, conversations with Costanzo Costantini, Editori Riuniti, Rome, 1996, p. 138)

Reviews

Casanova as he was never interested Fellini in the least. What he saw was another of the ghosts, the dreamlike projections, that habitually filled his imagination. Monster among monsters, disturbing larva among the many that crowd his reveries as an artist who grew up amid the religious conditioning of a small Adriatic town and landed in a Rome that always spoke to him especially as the privileged seat of an ecclesiastical society and custom.

(Mauro Manciotti, “Il Secolo XIX,” Dec. 22, 1976)

Casanova is, perhaps, Fellini’s best film since Otto e mezzo, probably the most free from Fellinism, certainly the most unified and compact (and there is little point in arguing whether it was really necessary to reach the 2 hours and 43 minutes in length) for richness and genius of figurative inventions, narrative tightness, wisdom in balancing the horrific with the tender and the fabulous with the ironic, ability to move from the caricatural to the visionary. It has always been one of the peculiarities of his talent, but here, even with some repetition, it is maintained at a high level of homogeneity, resting on a phonic fabric that, in its refined mystilinguism, is as admirable as the stupendous color palette of Rotunno’s photography.

(Morando Morandini, “Il Giorno,” Dec. 11, 1976)

Casanova is not a cinematic novel; it has no logical progression or real narrative links. The connections between the nine or ten chapters are quick and precarious, reminiscent of captions in “comics.” Federico Fellini’s grand circus belongs to the avant-garde, as the American filmmakers of the “underground” have well understood since the days of Eight and a Half. Despite the billions spent lavishly, we are not in the parts of what Flaubert called “industrial art”; we are closer to the monolithic, “privatism” and brazenness of an Andy Warhol. Therefore, the comparison that current events suggest between Barry Lindon and Casanova registers more dissimilarities than convergences. Kubrick takes seriously the nineteenth-century novel and the eighteenth-century setting, the sociological and political connotations of the affair: he has the air of having read and annotated an entire library, of having his own moral judgment about the era and the character. Fellini has flipped through the Casanovian Histoire like the phone book, has on the surface to offer nothing but impressions, resentments, mockery. However… There is a though here, too: if Kubrik’s re-enacted 1700s has its own deep cultural motivations, Fellini’s dreamed-up 1700s has the alarming and mysterious quality of a prophetic vision. Perhaps Jung would have said that Il Casanova is a prophecy about the past.

(Tullio Kezich, “La Repubblica,” Dec. 11, 1976)

Rich, multifaceted, varied in tone, perhaps not immune to some slackening of rhythm, Il Casanova imposes itself on our admiration especially in the parts in which its protagonist, as he grows older, acquires a humanity that was previously avariciously denied him, and thus engages us.

(Dario Zanelli, “Il Resto del Carlino,” Dec. 19, 1976)