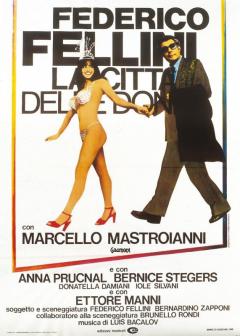

La città delle donne

Viewed censorship: 74981 27/03/1980

A train crosses the countryside: in a compartment snoozes Snàporaz, a distinguished 50-year-old man. A handsome stranger appears, and the man follows her. In the toilet, the two begin to flirt, then the woman suddenly steps off the train into a mysterious landscape. And behind her, Snàporaz. An international conference of feminists is taking place at the Grand Hotel Miramare. As the search for the mysterious passenger continues, Snàporaz, mistaken for a journalist, is attacked. Rescued by a soubrette on skates, in his escape he slips down the stairs and plummets into the cellars, where he meets a big man who, on a motorcycle, accompanies him to the station; the virago, as soon as they are in open country, tries to rape him. And Snàporaz flees again pursued by enraged women. He takes refuge in the castle of Dr. Katzone, his former schoolmate intent on celebrating his career as a libertine. There he meets his wife, who, drunk, covers him with insults, and the savior soubrettina. After retracing some stages of his sentimental upbringing, he is captured by feminists. His woman-shaped hot air balloon is deflated by machine gun fire. As he is plummeting, Snàporaz wakes up in the train, sitting in front of his wife, just before the convoy takes a long tunnel.

Crew

Director: Federico Fellini

Subject: Federico Fellini, Bernardino Zapponi

Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Bernardino Zapponi

Script collaboration: Brunello Rondi

Photography: Giuseppe Rotunno (Technovision – Color)

Cameraman: Gianni Fiore

Music: Luis Bacalov

Conductor: Gianfranco Plenizio

Songs: “Una donna senza uomo è” (words and music by Mary Francolao), “Donna addio” (verses by Antonio Amurri)

Ballet: Mirella Agujaro

Choreography consultant: Leonetta Bentivoglio

Set design: Federico Fellini

Set design: Dante Ferretti

Assistant set designer: Claude Chevant

Architect: Giorgio Giovannini

Assistant architect: Nazzareno Piana

Furniture: Bruno Cesari, Carlo Gervasi

Scenotechnician: Italo Tomassi

Sculptures: Giovanni Chianese

Paintings and frescoes: Rinaldo Geleng, Giuliano Geleng

Costumes: Gabriella Pescucci, Piattelli (for Mastroianni)

Costumes assistant: Maurizio Millenotti, Marcella De Marchis

Assistant Director: Maurizio Mein

Assistant director: Giovanni Bentivoglio, Anonio Amurri

Assistant director: Jean Louis Godfroy (2nd unit)

Special effects: Adriano Pischiutta

Sound: Tommaso Quattrini, Pierre Paul Marie Lorrain

Makeup: Rino Carboni

Editing: Ruggero Mastroianni

Editing assistant: Bruno Sarandrea, Roberto Puglisi

Editing assistant: Adriana Olasio

Executive producer: Franco Rossellini

General Organization: Lamberto Pippia

Production director: Francesco Orefici, Philippe Lorain Bernard (2nd unit)

Cast

Marcello Mastroianni : Snàporaz

Anna Prucnal : the wife of Snàporaz

Bernice Stegers : the lady on the train

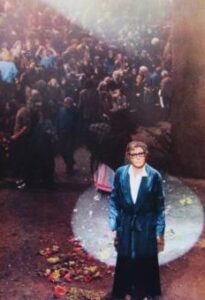

Ettore Manni : Dr. Sante Kartzone

Iole Silvani : the fat peasant motorcyclist

Donatella Damiani : Donatella the soubrettina

Fiammetta Baralla : “Ollio”

Helen G. Calzarelli

Catherine Carrel

Marcello Di Falco : homosexual at the Kartzone party

Silvana Fusacchia

Gabriella Giogelli : the fishwife

Dominique Labourier

Stephane Emilfork

Sylvie Mayer

Meerberger Nahyr

Sibyl Sedat

Katren Gebelein

Alessandra Panelli : housewife with baby in arms

Nadia Vasil

Loredana Solfizi

Fiorella Molinari

Rosaria Tafuri : Sara the second soubrettina

Sylvie Wacrenier

Carla Terlizzi : a feminist

Jill Lucas : one of the twins

Viviane Lucas : one of the twins

Mara Ciukleva : the eighty-five-year-old old lady

Mimmo Poli : participates in Kartzone’s party

Nello Pazzafini : appears in the final scene in the stadium

Armando Paracino : one of the three old magicians in the memory sequence

Umberto Zuanelli : one of the three old magicians in the memory sequence

Pietro Fumagalli : one of the three old magicians in the memory sequence

Awards

1980

Silver Ribbon for best director

Silver Ribbon for best cinematography

Silver Ribbon for best costumes

Peculiarites

“I have always been attracted to dreams, but of all my films only The City of Women is almost entirely a dream. Everything in the film has a hidden meaning, just like in a dream, except the beginning and the end, when Snaporaz is awake in the sleeping car. It is the nightmarish flap of Guido’s dream in Eight and a Half.”

(Charlotte Chandler, I, Federico Fellini, Mondadori, Milan, 1995, p. 2269)

Reviews

With more anguish than amusement, Fellini takes up the paths of Amarcord in a progressive loss of illusions about man’s role in the contemporary world. The film has the stated limitation of keeping within the autobiographical area, albeit capriciously dilated, without pushing its regressive force to that rediscovery of the “great dreams” of primitive humanity theorized by Jung.

(Tullio Kezich, The Brand New Millefilm. Five years at the cinema 1977-1982, Il Formichiere, Milan, 1983)

Having arrived at the threshold of old age […] Fellini as a director has (fortunately and ours) entered that splendid maturity in which a sacred monster manages to deepen its treasures of skill for the sole pleasure of doing so. There is, behind the festival of images, colors, a pleasure to make of cinema that from the first scenes becomes also yours, as a spectator, as you have not happened to try for a long time. Then what do you care if Fellini conceptually discovers hot water? You let yourself be carried away by the ride of inventions, and you can still amaze yourself (like a little boy who recently discovered cinema), at every sequence, at every shot. If in the City of women the suspense for the story, or for the ingredients (you do not care anything about how they will end Snàporaz or Katzone, you know very well that at a given point will arrive Rimini and the extras busty) there is the suspence of the images, of the scenic finds (you warn very well that Fellini is going to invent, but the invention you never know how and to what point it arrives to you). (Giorgio Carbone, “The Night”, Milan, 29 March 1980)

A fairy tale that Fellini enjoyed telling him (to the viewer) intentionally retracing all the stages of his cinema, here giving space, once again, to memories, as in Otto e mezzo and Amarcord, there making the point again on the present, as in La Dolce Vita and in Prova d’orchestra, alternating the nightmare to the dream, the vision to the joke and the anecdote, multiplying and varying languages and techniques, rediscovering and rereading the imagined and the real with an inspiration and a fertility of inventions to leave often fascinated and amazed.

(Gian Luigi Rondi, “Il Tempo”, Rome, 29 March 1980)

Opera […] untied but in its own coherent way, united by the extraordinary catalogue of unexpected and stimulating images, The City of Women is Fellini’s most imaginative and unbridled film, what does not mean that it is the best. Some parts repeat, even if dilated and refined, some recurring themes of the director (Rimini, the amusement park), so that it cannot be said that the originality of the finds can always hide some drop in tone and even taste. It is however a work in front of which it is difficult to get bored, provided […] not to practice exegesis unnecessarily punctilious, but to surrender to the pure enjoyment of the images.

(Angelo Solmi, “Today”, 18 April 1980)

“What kind of film is this?” she asks at some point in the Snàporaz-Fellini story. We reply that, despite some excess of greedy figurativeness, La città delle donne is a great film where, beyond the metaphor, pitiless as much with the woman as with the man, we find some components of the best Fellini: the mythological inspiration of the Dolce vita, the magical thrill of Juliet of the spirits, the nostalgia of Amarcord, the fairytale ambiguity of Otto and a half, of which it can be said the continuation.

(Domenico Meccoli, “Epoca”, 5 April 1980)