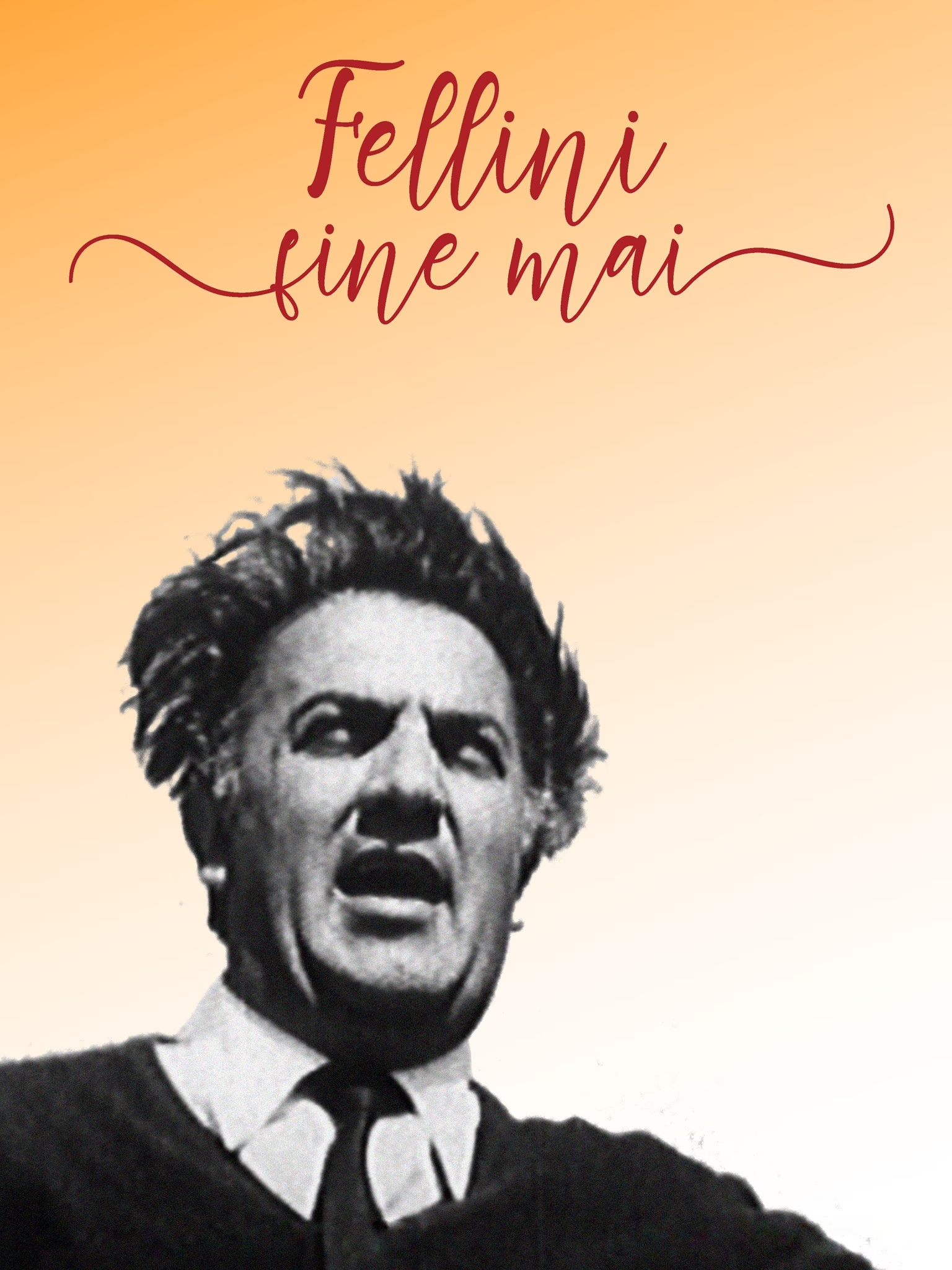

The 2025 Fellini Award to Alfonso Cuarón

The Fellini Award restarts with Alfonso Cuarón

Sunday, 7 December (6 PM) at the Galli Theatre in Rimini, the presentation of the award to one of the most acclaimed contemporary filmmakers

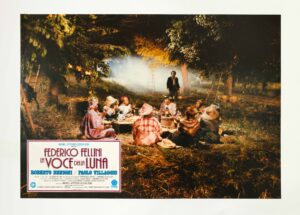

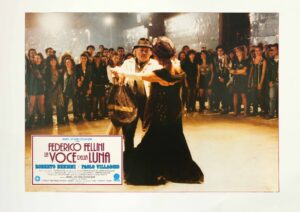

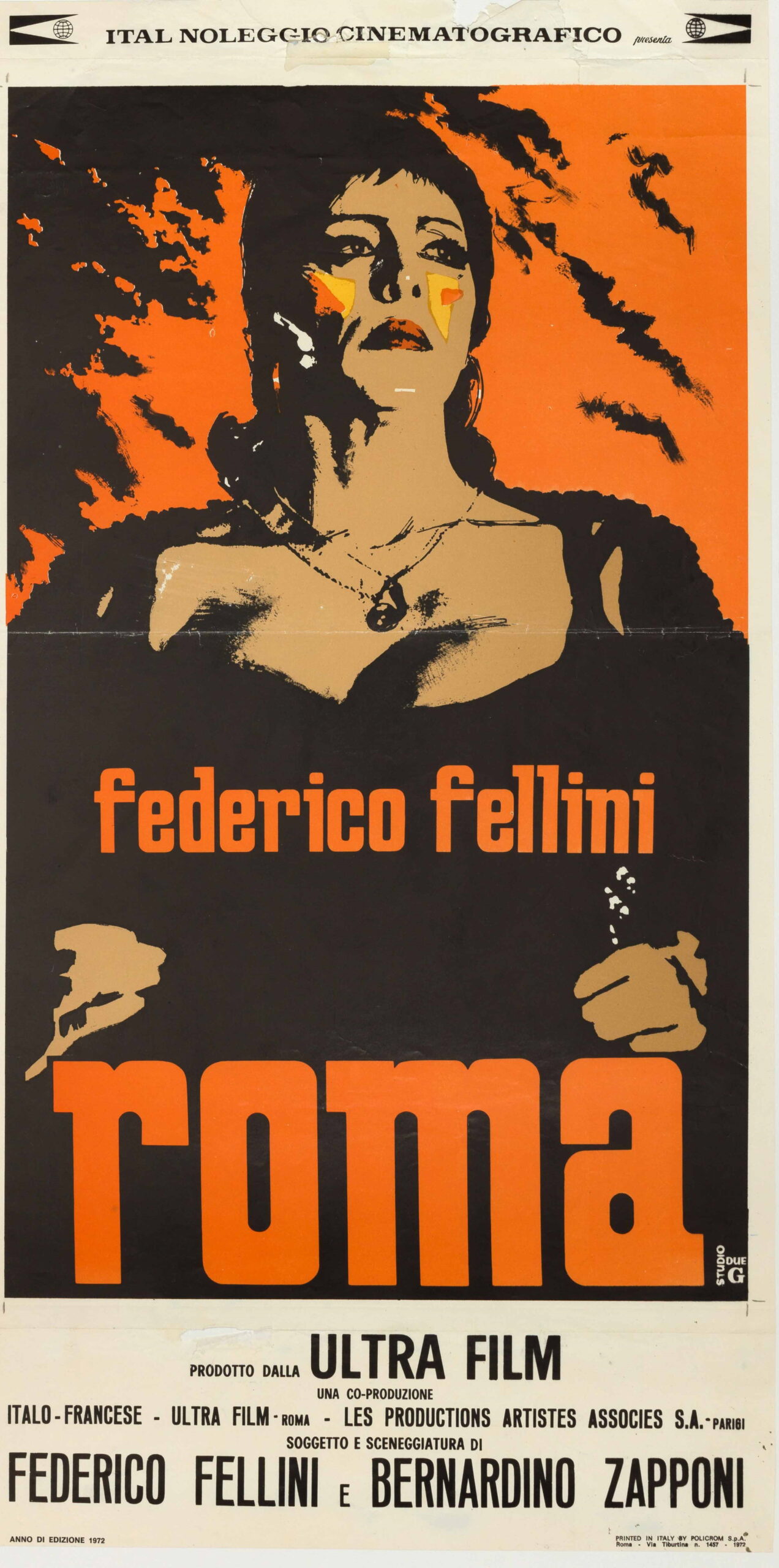

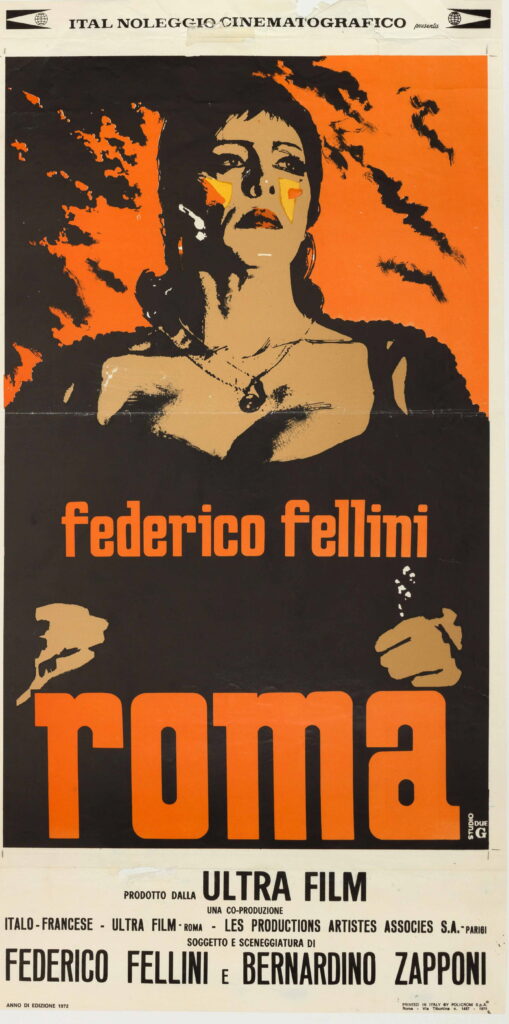

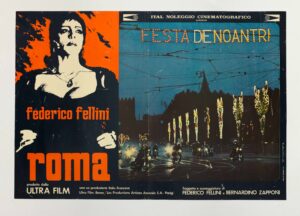

In the evening, the director will introduce his multi-award-winning film Roma at Cinema Fulgor

From Saturday, 6 December, a series of screenings between the Cineteca and the Cinemino featuring the Mexican filmmaker’s works in dialogue with the oeuvre of Federico Fellini

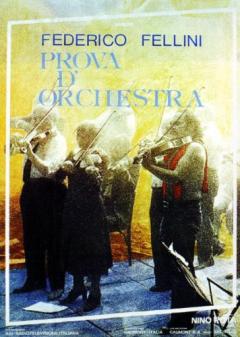

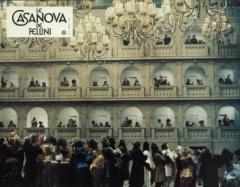

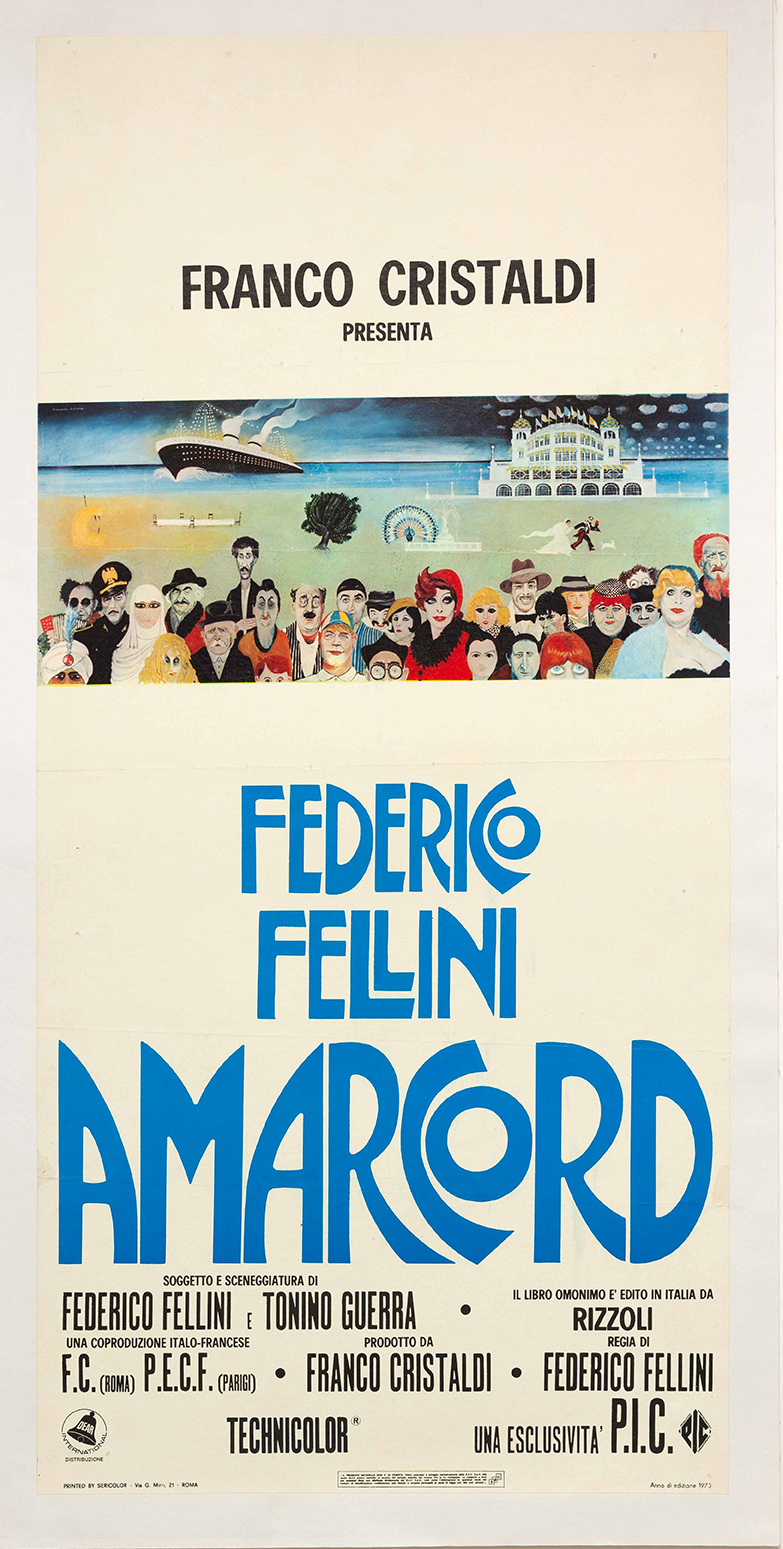

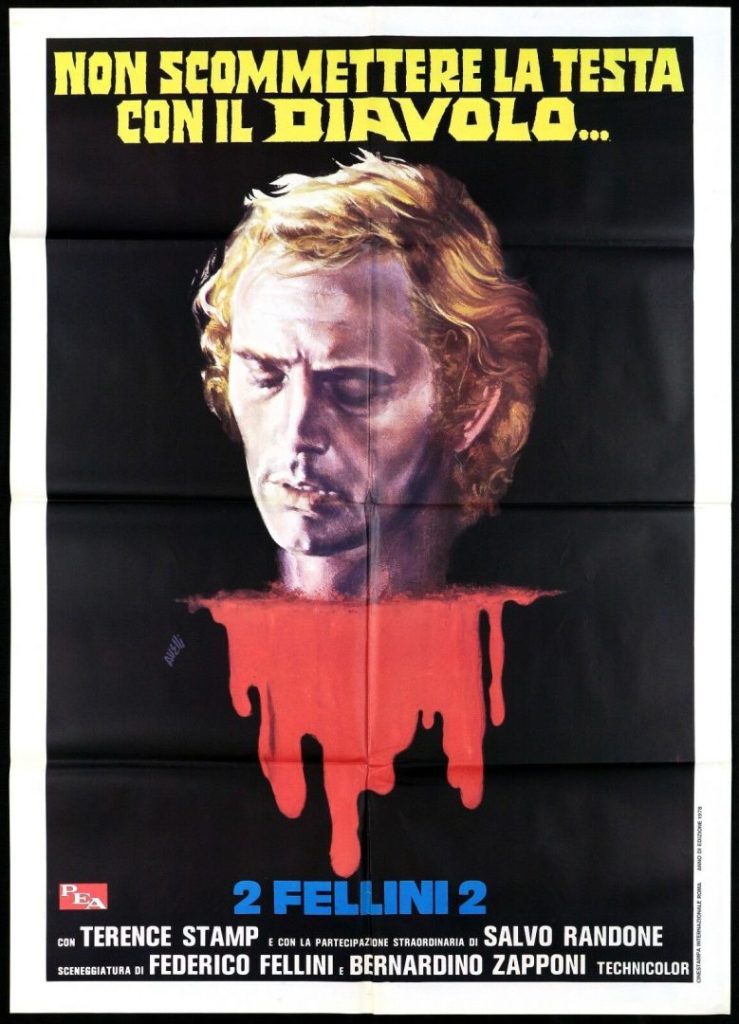

Federico Fellini and Alfonso Cuarón: two generations, two visions of cinema and reality, two poetic worlds intertwining, for the first time, in Rimini. It will be an ideal dialogue of images, words and dreams between the Maestro from Rimini and the Mexican director and screenwriter that will shape the “reborn” Fellini Award, presented in this first edition of its “new course” to one of the most appreciated contemporary filmmakers.

Cuarón is expected in Rimini on Sunday, 7 December (6 PM), when he will take the stage of the Amintore Galli Theatre for an in-depth conversation with Gian Luca Farinelli, director of the Cineteca di Bologna Foundation and artistic coordinator of the Award. A dialogue to explore the relationships and influences linking Cuarón to Fellini, “who – as the director himself explained – has influenced so much, since my earliest childhood, my love for cinema.” The Mayor, Jamil Sadegholvaad, will then present the filmmaker with the award that the City of Rimini has decided to relaunch fourteen years after its last edition, thanks to the renewed and valuable collaboration with the Bologna Cineteca.

Afterwards, at 8 PM, the event will move to the quintessential “Fellinian” cinema, the Fulgor, where Cuarón will introduce the screening of Roma, the 2018 film that earned him the Oscar and the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Alfonso Cuarón will then be in Bologna the following day, Monday, 8 December, where at Cinema Modernissimo he will present Roma and Jonas qui aura 25 ans en l’an 2000 by Alain Tanner, a director now almost forgotten, a “film of the heart” that Cuarón himself is helping to rediscover.

Book your seat here for the award ceremony at the Galli Theatre

Book your seat here for the screening at Cinema Fulgor

Admission will also be possible without reservation, with priority given to those who booked, until all seats are filled.

The Fellini Award Hall of Fame

The Fellini Award was first established by the City in 1994, with John Turturro as its first recipient, followed in the following years by Kathryn Bigelow (1995), Emir Kusturica (1996) and John Landis (1997). It was later the “Federico Fellini Foundation” that reinstated the Award in 2005, presenting it that year to Martin Scorsese, followed by Roman Polanski (2006), Ermanno Olmi (2007), Tullio Pinelli (2008) and Sidney Lumet (2009). The last two editions of the award coincided with the final two years of activity of the Fellini Foundation and saw Paolo Sorrentino (2010) and Terry Gilliam (2011) honoured in Rimini.

Alfonso Cuarón will therefore be the twelfth artist to enter the Fellini Award’s Hall of Fame.

The Fellini Award is organised by the City of Rimini and the Fellini Museum with the Cineteca di Bologna Foundation, in collaboration with Apt Servizi Emilia-Romagna and VisitRomagna.